Program

| The Mass (2021) |

| I. Kyrie |

| II. Gloria |

| III. Laudamus Te |

| IV. Domine Deus |

| V. Qui Tollis |

| VI. Cum sancto spiritus |

| VII. Credo |

| VIII. Et Incarnatus Est |

| IX. Et Resurrexit |

| X. Credo in spiritum sanctum |

| XI. Confiteor |

| XII. Sanctus |

| XIII. Osanna I |

| XIV. Benedictus |

| XV. Osanna II |

| XVI. Agnus Dei |

| Patrick Cassidy, composer |

|

Martin Sheen, guest host David Harris, conductor Christoph Bull, organ |

|

Laude and the Cathedral Choir: Laurel Irene, Molly Pease, Elizabeth Anderson, Tiffany Ho, David García Saldaña, James Hayden, Ianthe Marini, and Fahad Siadat; soloists |

I’ve had the pleasure of working with David Harris for over 10 years and during that time we’ve collaborated with hundreds of composers on the premieres of their music. So I wasn’t surprised when he told me he wanted to premiere a new setting of the Catholic mass by Patrick Cassidy. But when he told me he wanted to make a studio album remotely, with each singer recording their part individually at home, I was skeptical it would be of professional quality.

Allow me to describe the process of making a virtual recording. Every week I would receive a musical score filled with notes and a track with a click, guiding vocals, and accompaniment. I’d set up a mini recording studio in my house, waiting for a quiet enough hour where I could record my part, listen to what I’d sung, go back, and re-record any mistakes or unsatisfactory sections. Our editors and engineers would then take each individual recording and stitch them together to create a complete choral sound, and each week we waited to hear the final result, hoping no one would call us in a panic to re-record something we got wrong.

Making music like this is a lonely and tedious chore. You know that experience of hearing yourself on your answering machine and your own voice sounds flat and strange? Recording music in this way is like that x 100. It’s all the most aggravating parts of ensemble singing like fussing over notes, rhythms, and other minutiae, and none of the camaraderie and joy of the miraculous experience at the heart of making music together as a group. That doesn’t account for the emotional toll either: the terrible loneliness of recording alone in my home, or hearing the sound of this fabulous organ and the disembodied voices of my friends through my headphones, which served as a stark reminder of the space in which we were not allowed to gather as a community.

We recorded 3 to 4 songs like this every week for a year and a half making over 200 virtual choir recordings. We also got very good at it, so when it was time to record The Mass, we were pros. I’m proud to say we learned how to make not just coherent recordings, but ones that captured some of the mystery and expressiveness of live performance.

It’s hard for me to honestly say that the end result was worth what we went through to achieve it (even though our first single hit #1 on the Apple Sacred Music charts!). For choral singers, people who have come to rely on this communal art form as a way to connect with their fellow human beings, the last two years were nothing less than traumatic. What I can say is that when we finally gathered together again, after all those long months, and sang The Mass in person, the piece was nearly unrecognizable to me.

Suddenly, the glacial lines that seemed laborious when singing them by myself became meditative, the long phrases were supported and sustained by many singers on a part, the individual lines had context, depth and meaning, and I found myself in the middle of a contradiction common in choral music. On one hand I was a single voice, an independent melodic line riding on top of a sonic wave. On the other hand, I was an invisible mote inside a giant texture; one voice among dozens, one note in a much larger harmony.

I didn’t understand this during the recording process. It was only while being inside the piece itself; the full, complete, acoustic event, that I experienced a core truth embedded in musical performance: that while every sound I make is complete and whole by itself, it is also a very small contribution to something greater than the sum of its parts.

I can’t think of a better metaphor for a beloved community, one like FCCLA, that invites people from different backgrounds, lifestyles, and beliefs who align with a shared mission of interpersonal uplift, justice, and equality to bring their individual voices and contribute to a larger work that is also greater than the sum of its parts. I think this is what the Sufi poet Attar means when he declares “Unity in Diversity, that is oneness”.

And this notion of community, of unity in diversity, ultimately reflects the very heart of what “The Mass” and “the liturgy” are about. You see, the word liturgy itself comes from the Ancient Greek leitourgia which means "work for the people". It is a literal translation of the two words "litos ergos" or "public service".

The etymology of “The Mass” comes from the dismissal at the end of the rite “Ite, missa est" which means "Go, it has been sent." The 9th Century text titled ‘The Divine Office’ explains the word as “a 'sending', that which sends us towards God". May I suggest that this liturgical work is not contained within these walls, that to enact the liturgy is not a secret rite held up by the priesthood for those initiated into a particular belief structure, but rather that such a gathering is preparation for the work we will do when we walk out these doors and back into the world.

Such ‘sending forth’ is possible wherever people gather to realign themselves with each other in mutual uplift, whenever we collectively turn our focus inward with the intent of generating the seeds of external change. This work is a harnessing; a preparation for the sending when we take our newly recalibrated selves as a people, and turn towards the world with the intent of simply making it a better place.

Or, as the Irish proverb says, “It is in the shelter of one another that the people live”.

May the presentation of this work be such a public service, one that sends us into the world towards each other, and the great mystery between us.

Allow me to describe the process of making a virtual recording. Every week I would receive a musical score filled with notes and a track with a click, guiding vocals, and accompaniment. I’d set up a mini recording studio in my house, waiting for a quiet enough hour where I could record my part, listen to what I’d sung, go back, and re-record any mistakes or unsatisfactory sections. Our editors and engineers would then take each individual recording and stitch them together to create a complete choral sound, and each week we waited to hear the final result, hoping no one would call us in a panic to re-record something we got wrong.

Making music like this is a lonely and tedious chore. You know that experience of hearing yourself on your answering machine and your own voice sounds flat and strange? Recording music in this way is like that x 100. It’s all the most aggravating parts of ensemble singing like fussing over notes, rhythms, and other minutiae, and none of the camaraderie and joy of the miraculous experience at the heart of making music together as a group. That doesn’t account for the emotional toll either: the terrible loneliness of recording alone in my home, or hearing the sound of this fabulous organ and the disembodied voices of my friends through my headphones, which served as a stark reminder of the space in which we were not allowed to gather as a community.

We recorded 3 to 4 songs like this every week for a year and a half making over 200 virtual choir recordings. We also got very good at it, so when it was time to record The Mass, we were pros. I’m proud to say we learned how to make not just coherent recordings, but ones that captured some of the mystery and expressiveness of live performance.

It’s hard for me to honestly say that the end result was worth what we went through to achieve it (even though our first single hit #1 on the Apple Sacred Music charts!). For choral singers, people who have come to rely on this communal art form as a way to connect with their fellow human beings, the last two years were nothing less than traumatic. What I can say is that when we finally gathered together again, after all those long months, and sang The Mass in person, the piece was nearly unrecognizable to me.

Suddenly, the glacial lines that seemed laborious when singing them by myself became meditative, the long phrases were supported and sustained by many singers on a part, the individual lines had context, depth and meaning, and I found myself in the middle of a contradiction common in choral music. On one hand I was a single voice, an independent melodic line riding on top of a sonic wave. On the other hand, I was an invisible mote inside a giant texture; one voice among dozens, one note in a much larger harmony.

I didn’t understand this during the recording process. It was only while being inside the piece itself; the full, complete, acoustic event, that I experienced a core truth embedded in musical performance: that while every sound I make is complete and whole by itself, it is also a very small contribution to something greater than the sum of its parts.

I can’t think of a better metaphor for a beloved community, one like FCCLA, that invites people from different backgrounds, lifestyles, and beliefs who align with a shared mission of interpersonal uplift, justice, and equality to bring their individual voices and contribute to a larger work that is also greater than the sum of its parts. I think this is what the Sufi poet Attar means when he declares “Unity in Diversity, that is oneness”.

And this notion of community, of unity in diversity, ultimately reflects the very heart of what “The Mass” and “the liturgy” are about. You see, the word liturgy itself comes from the Ancient Greek leitourgia which means "work for the people". It is a literal translation of the two words "litos ergos" or "public service".

The etymology of “The Mass” comes from the dismissal at the end of the rite “Ite, missa est" which means "Go, it has been sent." The 9th Century text titled ‘The Divine Office’ explains the word as “a 'sending', that which sends us towards God". May I suggest that this liturgical work is not contained within these walls, that to enact the liturgy is not a secret rite held up by the priesthood for those initiated into a particular belief structure, but rather that such a gathering is preparation for the work we will do when we walk out these doors and back into the world.

Such ‘sending forth’ is possible wherever people gather to realign themselves with each other in mutual uplift, whenever we collectively turn our focus inward with the intent of generating the seeds of external change. This work is a harnessing; a preparation for the sending when we take our newly recalibrated selves as a people, and turn towards the world with the intent of simply making it a better place.

Or, as the Irish proverb says, “It is in the shelter of one another that the people live”.

May the presentation of this work be such a public service, one that sends us into the world towards each other, and the great mystery between us.

Program

| The Mass (2021) | Patrick Cassidy | |

|

I. Kyrie II. Gloria III. Laudamus Te IV. Domine Deus V. Qui Tollis VI. Cum sancto spiritus VII. Credo VIII. Et Incarnatus Est |

IX. Et Resurrexit X. Credo in spiritum sanctum XI. Confiteor XII. Sanctus XIII. Osanna I XIV. Benedictus XV. Osanna II XVI. Agnus Dei |

|

|

Martin Sheen, guest host David Harris, conductor Christoph Bull, organ Laude and the Cathedral Choir: Laurel Irene, Molly Pease, Elizabeth Anderson, Tiffany Ho, David García Saldaña, James Hayden, Ianthe Marini, and Fahad Siadat; soloists |

||

I’ve had the pleasure of working with David Harris for over 10 years and during that time we’ve collaborated with hundreds of composers on the premieres of their music. So I wasn’t surprised when he told me he wanted to premiere a new setting of the Catholic mass by Patrick Cassidy. But when he told me he wanted to make a studio album remotely, with each singer recording their part individually at home, I was skeptical it would be of professional quality.

Allow me to describe the process of making a virtual recording. Every week I would receive a musical score filled with notes and a track with a click, guiding vocals, and accompaniment. I’d set up a mini recording studio in my house, waiting for a quiet enough hour where I could record my part, listen to what I’d sung, go back, and re-record any mistakes or unsatisfactory sections. Our editors and engineers would then take each individual recording and stitch them together to create a complete choral sound, and each week we waited to hear the final result, hoping no one would call us in a panic to re-record something we got wrong.

Making music like this is a lonely and tedious chore. You know that experience of hearing yourself on your answering machine and your own voice sounds flat and strange? Recording music in this way is like that x 100. It’s all the most aggravating parts of ensemble singing like fussing over notes, rhythms, and other minutiae, and none of the camaraderie and joy of the miraculous experience at the heart of making music together as a group. That doesn’t account for the emotional toll either: the terrible loneliness of recording alone in my home, or hearing the sound of this fabulous organ and the disembodied voices of my friends through my headphones, which served as a stark reminder of the space in which we were not allowed to gather as a community.

We recorded 3 to 4 songs like this every week for a year and a half making over 200 virtual choir recordings. We also got very good at it, so when it was time to record The Mass, we were pros. I’m proud to say we learned how to make not just coherent recordings, but ones that captured some of the mystery and expressiveness of live performance.

It’s hard for me to honestly say that the end result was worth what we went through to achieve it (even though our first single hit #1 on the Apple Sacred Music charts!). For choral singers, people who have come to rely on this communal art form as a way to connect with their fellow human beings, the last two years were nothing less than traumatic. What I can say is that when we finally gathered together again, after all those long months, and sang The Mass in person, the piece was nearly unrecognizable to me.

Suddenly, the glacial lines that seemed laborious when singing them by myself became meditative, the long phrases were supported and sustained by many singers on a part, the individual lines had context, depth and meaning, and I found myself in the middle of a contradiction common in choral music. On one hand I was a single voice, an independent melodic line riding on top of a sonic wave. On the other hand, I was an invisible mote inside a giant texture; one voice among dozens, one note in a much larger harmony.

I didn’t understand this during the recording process. It was only while being inside the piece itself; the full, complete, acoustic event, that I experienced a core truth embedded in musical performance: that while every sound I make is complete and whole by itself, it is also a very small contribution to something greater than the sum of its parts.

I can’t think of a better metaphor for a beloved community, one like FCCLA, that invites people from different backgrounds, lifestyles, and beliefs who align with a shared mission of interpersonal uplift, justice, and equality to bring their individual voices and contribute to a larger work that is also greater than the sum of its parts. I think this is what the Sufi poet Attar means when he declares “Unity in Diversity, that is oneness”.

And this notion of community, of unity in diversity, ultimately reflects the very heart of what “The Mass” and “the liturgy” are about. You see, the word liturgy itself comes from the Ancient Greek leitourgia which means "work for the people". It is a literal translation of the two words "litos ergos" or "public service".

The etymology of “The Mass” comes from the dismissal at the end of the rite “Ite, missa est" which means "Go, it has been sent." The 9th Century text titled ‘The Divine Office’ explains the word as “a 'sending', that which sends us towards God". May I suggest that this liturgical work is not contained within these walls, that to enact the liturgy is not a secret rite held up by the priesthood for those initiated into a particular belief structure, but rather that such a gathering is preparation for the work we will do when we walk out these doors and back into the world.

Such ‘sending forth’ is possible wherever people gather to realign themselves with each other in mutual uplift, whenever we collectively turn our focus inward with the intent of generating the seeds of external change. This work is a harnessing; a preparation for the sending when we take our newly recalibrated selves as a people, and turn towards the world with the intent of simply making it a better place.

Or, as the Irish proverb says, “It is in the shelter of one another that the people live”.

May the presentation of this work be such a public service, one that sends us into the world towards each other, and the great mystery between us.

Allow me to describe the process of making a virtual recording. Every week I would receive a musical score filled with notes and a track with a click, guiding vocals, and accompaniment. I’d set up a mini recording studio in my house, waiting for a quiet enough hour where I could record my part, listen to what I’d sung, go back, and re-record any mistakes or unsatisfactory sections. Our editors and engineers would then take each individual recording and stitch them together to create a complete choral sound, and each week we waited to hear the final result, hoping no one would call us in a panic to re-record something we got wrong.

Making music like this is a lonely and tedious chore. You know that experience of hearing yourself on your answering machine and your own voice sounds flat and strange? Recording music in this way is like that x 100. It’s all the most aggravating parts of ensemble singing like fussing over notes, rhythms, and other minutiae, and none of the camaraderie and joy of the miraculous experience at the heart of making music together as a group. That doesn’t account for the emotional toll either: the terrible loneliness of recording alone in my home, or hearing the sound of this fabulous organ and the disembodied voices of my friends through my headphones, which served as a stark reminder of the space in which we were not allowed to gather as a community.

We recorded 3 to 4 songs like this every week for a year and a half making over 200 virtual choir recordings. We also got very good at it, so when it was time to record The Mass, we were pros. I’m proud to say we learned how to make not just coherent recordings, but ones that captured some of the mystery and expressiveness of live performance.

It’s hard for me to honestly say that the end result was worth what we went through to achieve it (even though our first single hit #1 on the Apple Sacred Music charts!). For choral singers, people who have come to rely on this communal art form as a way to connect with their fellow human beings, the last two years were nothing less than traumatic. What I can say is that when we finally gathered together again, after all those long months, and sang The Mass in person, the piece was nearly unrecognizable to me.

Suddenly, the glacial lines that seemed laborious when singing them by myself became meditative, the long phrases were supported and sustained by many singers on a part, the individual lines had context, depth and meaning, and I found myself in the middle of a contradiction common in choral music. On one hand I was a single voice, an independent melodic line riding on top of a sonic wave. On the other hand, I was an invisible mote inside a giant texture; one voice among dozens, one note in a much larger harmony.

I didn’t understand this during the recording process. It was only while being inside the piece itself; the full, complete, acoustic event, that I experienced a core truth embedded in musical performance: that while every sound I make is complete and whole by itself, it is also a very small contribution to something greater than the sum of its parts.

I can’t think of a better metaphor for a beloved community, one like FCCLA, that invites people from different backgrounds, lifestyles, and beliefs who align with a shared mission of interpersonal uplift, justice, and equality to bring their individual voices and contribute to a larger work that is also greater than the sum of its parts. I think this is what the Sufi poet Attar means when he declares “Unity in Diversity, that is oneness”.

And this notion of community, of unity in diversity, ultimately reflects the very heart of what “The Mass” and “the liturgy” are about. You see, the word liturgy itself comes from the Ancient Greek leitourgia which means "work for the people". It is a literal translation of the two words "litos ergos" or "public service".

The etymology of “The Mass” comes from the dismissal at the end of the rite “Ite, missa est" which means "Go, it has been sent." The 9th Century text titled ‘The Divine Office’ explains the word as “a 'sending', that which sends us towards God". May I suggest that this liturgical work is not contained within these walls, that to enact the liturgy is not a secret rite held up by the priesthood for those initiated into a particular belief structure, but rather that such a gathering is preparation for the work we will do when we walk out these doors and back into the world.

Such ‘sending forth’ is possible wherever people gather to realign themselves with each other in mutual uplift, whenever we collectively turn our focus inward with the intent of generating the seeds of external change. This work is a harnessing; a preparation for the sending when we take our newly recalibrated selves as a people, and turn towards the world with the intent of simply making it a better place.

Or, as the Irish proverb says, “It is in the shelter of one another that the people live”.

May the presentation of this work be such a public service, one that sends us into the world towards each other, and the great mystery between us.

Performers

|

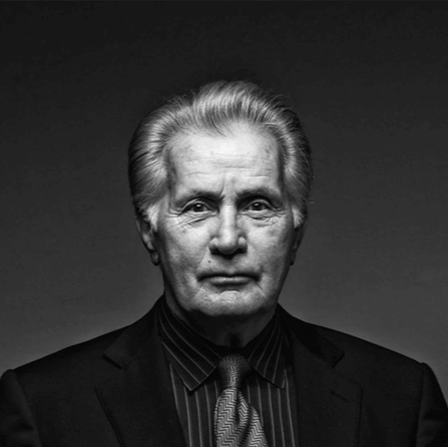

Martin Sheen |

Martin Sheen is an award winning actor and Hollywood star. He has appeared in some of the biggest movies of the past sixty years, and has truly made a mark on the industry. With over two hundred and fifty acting credits to his name, Sheen will always be remembered for his impressive repertoire. Sheen has been in many impressive roles over the span of his career, making it difficult to pick highlights, but he has certainly appeared in some classic movies over the years. He found success in the 1970 movie, Catch-22, and also starred in Badlands in 1973. In more recent years, he has starred alongside the likes of Leonardo DiCaprio and Matt Damon in celebrated crime thriller, The Departed, and the 2012 superhero film, The Amazing Spiderman. It’s safe to say these roles established him as a key figure in Hollywood and made him a household name. Sheen has also appeared in plenty of well-known TV shows. He spent five years on the set of Grace and Frankie, a comedy show starring Jane Fonda and Lily Tomlin. He also won a Golden Globe for his performance in The West Wing, earning himself the award for The Best Performance by an Actor in a TV Series. In addition to his film and TV success, Sheen has also been a regular voice actor for the well-known game series, Mass Effect. |

|

The members of Laude represent some of the brightest vocal and choral stars in Los Angeles. Ensemble and business leaders, composers, soloists, film and stage actors, and instrumentalists make up this robust chamber group, lending it noted flexibility and strength. Laude members sing with the FCCLA Cathedral Choir as section leaders in addition to meeting on their own to present more intimate musical experiences. Each member also frequently presents solo features from the breadth of their professional acumen. |

|

David Harris specializes in new music, American music, and the intricacies of communication in singing and conducting. Through innovation, performance, and research, David enlivens community through the power of music. Having been called the “Thomas Edison of vocal music” by those close to him, and “one of the most compelling conductors in America”, his favorite accolade comes from a New Year’s Eve Bostonian who casually offered that he “looks like a guy who could wear suede in the rain and not get wet.” An advocate of new music, David has premiered hundreds of pieces for vocal and instrumental ensembles, and for the theater. He shares his creative passion with the composers, performers and audiences who bring life to new work, guiding them in the unique discovery of self found in new composition. |

|

Christoph Bull likes organ music, rock music and rocking organ music. He has concertized around the world, including Europe, Russia, India, Taiwan, China, Japan, El Salvador and many U.S. states. He’s performed at national and regional conventions of the American Guild of Organists and the Organ Historical Society. Venues Dr Bull has performed at include The National Concert Hall in Taipei, Shanghai Conservatory, the Shumei Temple in Misono (Japan), Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, Lincoln Center in New York City, Segerstrom Concert Hall in Costa Mesa, the Cathedrals of Moscow, Los Angeles, Saint-Denis and Salzburg as well as rock clubs like The Viper Room, The Roxy and The Whisky in Los Angeles. Christoph Bull recorded the first album featuring the organ at Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, entitled First & Grand. His music has been broadcast on KCRW, on Classical KUSC and the Minnesota Public Radio program “Pipedreams”. He recorded the pipe organ parts for the latest Ghostbusters and Transformers movies at First Congregational Church of Los Angeles. He also worked as organ consultant on Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report and recorded for Robin Williams’ last TV Show The Crazy Ones. He has performed with George Clinton and recorded with Bootsy Collins (both Parliament Funkadelic) and consulted for Harry Connick Jr. Christoph Bull is university organist and organ professor at UCLA as well as organist-in-residence at First Congregational Church of Los Angeles, regularly playing one of the largest pipe organs in the world. |

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

|

The Resonance Collective